Search

Sorry, no results found. Please try adjusting your search.

This project re-imagines a car-centric streetscape of two city blocks and a plaza as a new public realm aligned with the city’s vibrant and diverse community

Proactive community engagement drove the success of this work: over 70 pop-up and prototyping events, one-on-one stakeholder meetings, artist sessions, and other engagement events captured a true understanding of the community’s needs and desires for this project.

The project pioneers a curbless street design, integrates dramatic public art installations from local and internationally known artists, and utilizes custom-designed accessible site furniture. Cutting-edge sustainability strategies promote greenery and reduce stormwater runoff and ice-melting salt usage.

The project pioneers a curbless street design, integrates dramatic public art installations from local and internationally known artists, and utilizes custom-designed accessible site furniture. Cutting-edge sustainability strategies promote greenery and reduce stormwater runoff and ice-melting salt usage.

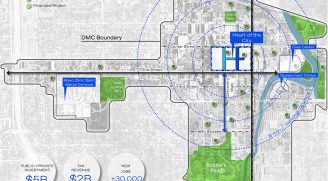

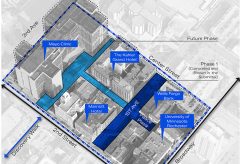

The new public realm aligns with the city’s vibrant community that welcomes millions of guests each year (Mayo Clinic patients and their families). Our client, Destination Medical Center (DMC), is a non-profit organization implementing a $5.6 billion, 20-year economic development initiative. Heart of the City is Phase 1 of a public realm master plan.

The new public realm aligns with the city’s vibrant community that welcomes millions of guests each year (Mayo Clinic patients and their families). Our client, Destination Medical Center (DMC), is a non-profit organization implementing a $5.6 billion, 20-year economic development initiative. Heart of the City is Phase 1 of a public realm master plan.

Since opening May 2022, this project has fulfilled its main goal of activating downtown Rochester. The plaza has held 100+ events, and averages 2,500+ daily pedestrians.

Since opening May 2022, this project has fulfilled its main goal of activating downtown Rochester. The plaza has held 100+ events, and averages 2,500+ daily pedestrians.

The project site is adjacent to the Mayo Clinic’s campus. The road was wide and flanked with parking; most sidewalks were not ADA accessible; and there were no gathering places. These constrained, hardscape-dominated spaces created a drab, unwelcoming experience. We transformed this area through three main design processes: Creative Community Engagement, Make It About Art, Healthy Place for People and Nature.

Creative Community Engagement

Community engagement played a central part in understanding and addressing the needs of this project’s user groups (residents and Mayo Clinic visitors), and other stakeholders. The design team went beyond traditional engagement methods to meet the community on their terms. We held over 70 engagement sessions, including 35 one-on-one meetings with business and property-owners, 12 open house and art & design events, 12 pop-up events, 11 prototyping events, and 3 DMC discussions.

During one of the first engagement sessions, we summarized the public’s core project principles:

• Make It Rochester

• Make It A Destination

• Make It Big & Keep It Small

• Reveal The Unseen

• Make It About Life

• Make It About Art

• Make It About Healing

• Make It Inviting

• Embrace The North

• Make It Bright

• Make It Connected

• Make It Green

We gathered community feedback on site elements—including the desire for a performance stage. The community felt our first mock-up (a terraced viewing stage) blocked too much of the plaza. After more studies, we settled a bench system on rails that can be re-arranged to form a stage.

Creative Community Engagement

Community engagement played a central part in understanding and addressing the needs of this project’s user groups (residents and Mayo Clinic visitors), and other stakeholders. The design team went beyond traditional engagement methods to meet the community on their terms. We held over 70 engagement sessions, including 35 one-on-one meetings with business and property-owners, 12 open house and art & design events, 12 pop-up events, 11 prototyping events, and 3 DMC discussions.

During one of the first engagement sessions, we summarized the public’s core project principles:

• Make It Rochester

• Make It A Destination

• Make It Big & Keep It Small

• Reveal The Unseen

• Make It About Life

• Make It About Art

• Make It About Healing

• Make It Inviting

• Embrace The North

• Make It Bright

• Make It Connected

• Make It Green

We gathered community feedback on site elements—including the desire for a performance stage. The community felt our first mock-up (a terraced viewing stage) blocked too much of the plaza. After more studies, we settled a bench system on rails that can be re-arranged to form a stage.

Make It About Art:

The community wanted the plaza to capture the imaginations of visitors. With the help of an art curator, we were able to integrate public art from local and internationally renowned artists.

Peace Plaza acknowledges the site’s history as Dakota land through Ann Hamilton’s artwork Song for Water, which embeds Dr. Gwen Westerman’s poem De Wakpa Taŋka Odowaŋ / Song for the Mississippi River into a 200-foot-long plaza.

Peace Plaza acknowledges the site’s history as Dakota land through Ann Hamilton’s artwork Song for Water, which embeds Dr. Gwen Westerman’s poem De Wakpa Taŋka Odowaŋ / Song for the Mississippi River into a 200-foot-long plaza.

Eric Anderson’s “Wakefield” consists misting jets that are actuated by Mayo Clinic data: emitting mist for every first and last breath taken.

Eric Anderson’s “Wakefield” consists misting jets that are actuated by Mayo Clinic data: emitting mist for every first and last breath taken.

We redesigned the plinth for Peace Sculpture (1986) so people could view the sky through the structure of overlapping doves. This sculpture informed Inigo Manglano-Ovall‘s piece, “A Not So Private Sky”. His artwork creates a vertical element made of reflective materials that offers another experience of the sky.

We redesigned the plinth for Peace Sculpture (1986) so people could view the sky through the structure of overlapping doves. This sculpture informed Inigo Manglano-Ovall‘s piece, “A Not So Private Sky”. His artwork creates a vertical element made of reflective materials that offers another experience of the sky.

Healthy Place for People and Nature

A Mayo Clinic ADA specialist advised on universal design. We emphasized accessible circulation and site furniture—including custom wheelchair-friendly furniture and paving patterns that are easier for visually impaired people to navigate. We planted 117 street trees using soil cell systems. Pervious pavement allows stormwater to percolate down to the cells. Heated sidewalks throughout reduce the need for ice-melting salt—reducing stress on the trees.

Healthy Place for People and Nature

A Mayo Clinic ADA specialist advised on universal design. We emphasized accessible circulation and site furniture—including custom wheelchair-friendly furniture and paving patterns that are easier for visually impaired people to navigate. We planted 117 street trees using soil cell systems. Pervious pavement allows stormwater to percolate down to the cells. Heated sidewalks throughout reduce the need for ice-melting salt—reducing stress on the trees.